From vernacular to institutional

Towards the end of the 19th century the mineral springs in Bulgaria became the subject of increasingly more complex regulations, redefining the use of the resource on multiple levels including access, ownership and extraction.

Within the course of only a few decades, a centuries-old culture of vernacular remedial and social practices faded, along with the structures it was associated with – many Ottoman era hammams and outdoor pools were demolished and only on rare occasions were incorporated into the larger structures of modern baths. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, together with the construction of new bathing facilities, a framework of more rigid medical recommendations was being developed, attempting to pair the advancements in contemporary medicine with the specific healing properties of the local thermal springs. The access to the resource transitioned from its near-natural settings to the confines of established institutions where exposure and consumption could be carefully controlled and measured.

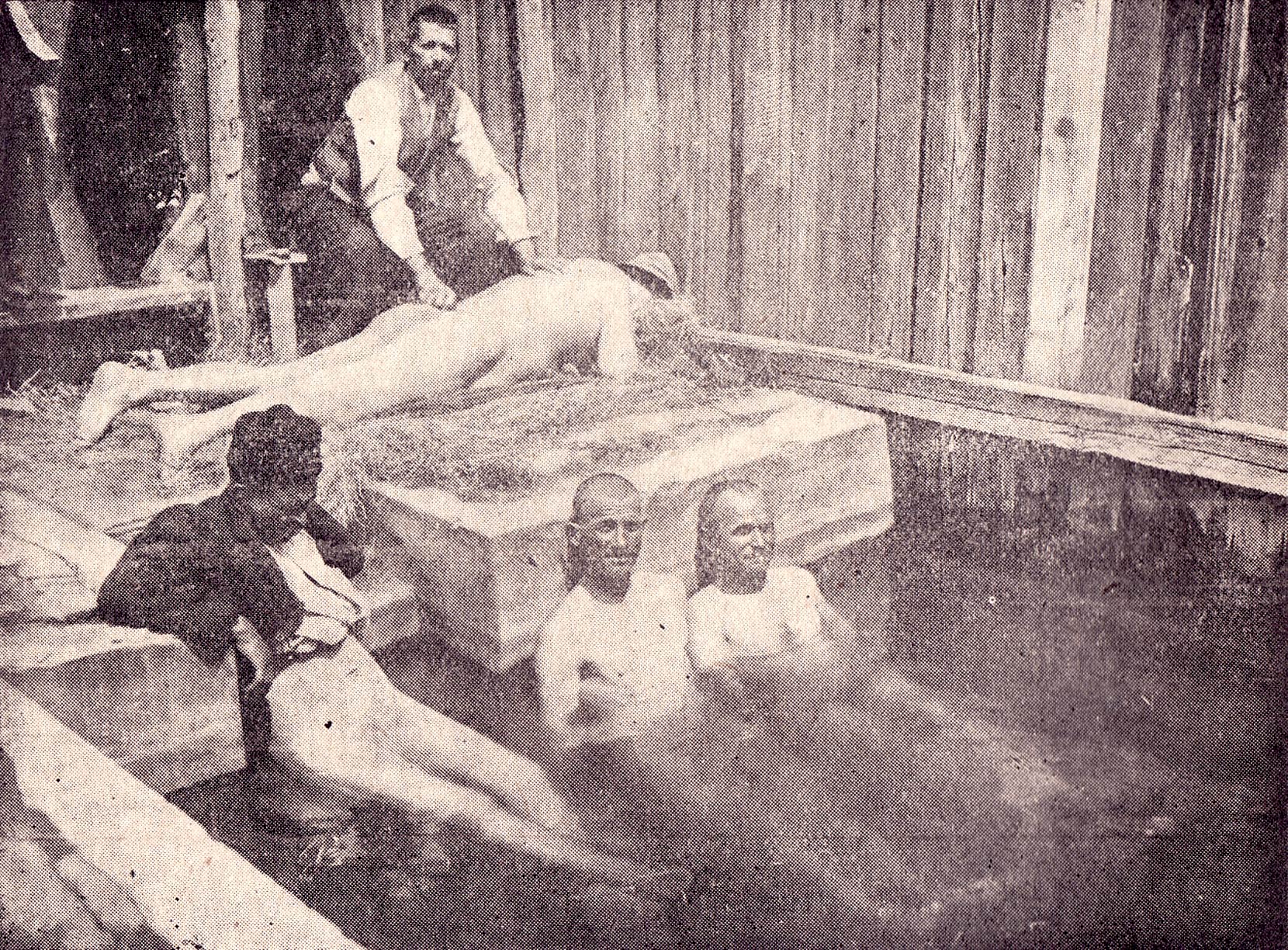

An improvised pool at the hot spring in Ovcha Kupel, Sofia, used before the modern thermal bath was built in 1933.

In the years after the Second World War a countrywide state-subsidized campaign for the improvement of the workers’ conditions was set in motion, with accessible healthcare being at the forefront of the efforts. The same period marked a surge in the planning and building of large scale balneosanatorial projects, aiming to significantly increase the capacity of the existing infrastructure, mediating the access to the healing waters. By now treatment had become a sequence of complex procedures requiring specific expertise and advanced medical equipment, often custom-designed for the needs of a given balneosanatorium. A single course of treatment would take 15 to 20 and occasionally up to 40 days in order to achieve lasting improvement. Such extended stays, in addition to a manifold increase in capacity, required an array of amenities, transforming small villages into busy resorts, ready with outdoors cinemas, stadia, restaurants, shops, farmer’s markets and beauty shops.

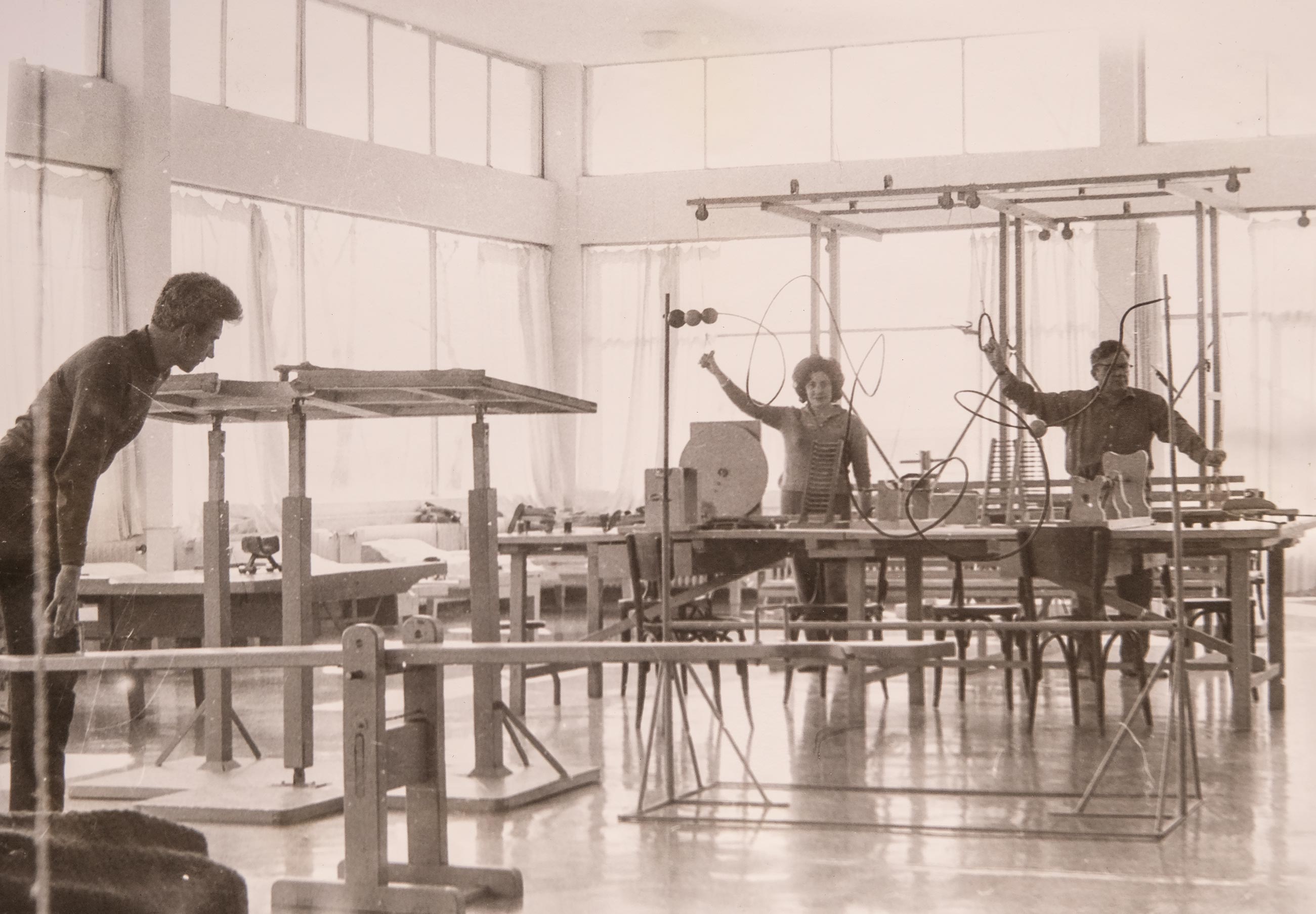

The balneosanatorium in Pavel Banya, completed in 1956, hosted workshops where

rehabilitation equipment could be designed and built, tailored to the specific

needs of the patients.

Pictured: a mechanotherapy room with patients exercising aided by devices designed by Dr. Georgi Gechev.

Private archive of Dr. Georgi Gechev. With the permission of Gergana Gecheva. First publication

Contested resources

The extensive balneosanatorial infrastructures required significant resources in order to maintain their operations. First signs of a system operating under pressure appeared in the late 1970s, in visitors’ accounts, describing their disappointment at the poor maintenance and compromised services of several thermal baths.

Seismic shifts in the political, economic and social landscapes in Eastern Europe in the years after 1989, and the subsequent “transition” period were decisive for the future of the majority of these complex infrastructures. Deregulation allowing for the privatization of state and municipally owned properties – land and buildings, saw many of the balneosanatorial centers close, with few of them retaining their functions today and the majority adding to the ubiquitous landscapes of contemporary ruins scattered across modern day Bulgaria.

Today a renewed interest in the thermal waters has triggered a new wave of urban transformations, creating unusual sights of unlikely cohabitations. Private hotels emerge in the vicinity of former large scale balneosanatoria - now vacant, or heritage buildings awaiting restoration now find their public green areas divided into sites ready for sale and redevelopment. Construction of new spa hotels often outpaces the limits of the available natural resource with a number of conflicts entering the public debate with greater intensity in recent years.

Pavel Banya, January 2021

Bathing and healing in southeast Bulgaria

The administrative region of southeast Bulgaria, covering an area of just below 20,000 km², is home to several balneological resorts, each specialized in the treatment of specific conditions. Pavel Banya, Burgas Mineral Baths, Stara Zagora Mineral Baths, Sliven Mineral Baths, and Stefan Karadzhovo underwent extensive redevelopment in the 20th century, as part of energetic public healthcare campaigns. Today only part of the infrastructures built in the past century remain accessible and operational, with the majority or all of the facilities in two of these resorts now closed, despite an abundant natural resource still present.

Few public thermal baths remain open today - in Banya (near Korten), Kazanlak and Ovoshnik. The Yagoda Thermal Bath is currently being restored and in Yambol awaiting its transformation after the natural resource was lost a few decades ago.

According to data from the Ministry of Environment and Water, the available thermal water flow totals 130 l/sec. ranging from 20.8 to 80˚C.

The 10 sites studied over the course of three months of fields work.

The findings will be gradually added to the platform - as case studies and archival references.

Literature

Богданова, Мара Никифорова [Bogdanova, Mara Nikiforova]. Минерална баня и курорт „Овча купел“ до София [The thermal bath and resort “Ovcha Kupel” near Sofia], Sofia, 1933

Гечев, Георги д-р [Gechev, Georgi, Dr]. Павел Баня [Pavel banya], Sofia: Медицина и физкултура, 1981

Гочев, Гочо [Gochev, Gocho]. История на Сливенските минерални бани [History of Sliven Mineral Baths], Sliven: Жажда, 2015

Димитрова, Светла [Dimitrova Svetla]. Старозагорските минерални бани, история в осем хилядолетия [Stara Zagora Mineral Baths, eight thousand years of history], Stara Zagora, 2017

Закон за топлите и студените минерални води [Hot and cold mineral springs decree]. Държавен вестник, year XIII, 13 Dec. 1891, #273

Source: Север +

Затвориха лековити басейни в Павел баня заради липса на минерална вода [Treatment pools closed in Pavel banya due to insufficient thermal water], Монитор, 19 Sept. 2019, #6868

Иванов, П. [Ivanov, P.] Казанлък в миналото и днес [Kazanlak in the past and today], book 2, Sofia: Придворна печатница, 1923

Книга за диагнозите и лечението на болни с решение на медицинската комисия към Ямболската минерална баня 1936-1945 година [Diagnoses and treatment, Medical committee at the Yambol Mineral Bath 1936-1945]. Archives State Agency - Yambol, Ф. 47К, оп. 2, а.е. 7

Николова, Ирена и Димитрина Тодорова [Nikolova, Irena and Todorova, Dimitrina]. Да подадем ръка на ...Сливенските минерани бани, Сливенско дело [Let's stand by ...the Sliven Mineral Baths], 23 May 1987, #60

Станчев, Ив. С.[Stanchev, Iv. S.] Сливенски минерални бани [Sliven Mineral baths], Sliven: Курортно бюро при Сливенската община, 1936

Тошев, Андрей [Toshev, Andrey]. Ранни спомени 1873-1879 [Early memories 1873-1897] Source: dolap.bg

Христов, Хр. [Hristov, Hr.] Разпределениe нa „дара божи“ противопоставя болница и хотели в Павел баня. Старозагoрски новини, №141. 20 Sept. 2019