Nature – Culture – Nature

“The summer crowds would need many hotels, parks, entertainment, fast commutes

from Sliven…”

G. Kozarev, The newly built thermal bath near Sliven, Magazine of

the Bulgarian Architecture and Engineering Association, Sofia 1902, p. 142

“This year’s great numbers of visitors at Sliven Mineral Baths are more than

satisfactory. The hotels are full, many guests are staying in tents and some

were sent back.”

“Our mineral baths”, Iztok, 1940, #281, p. 2

“Summer and winter, it is always full of people here. And it will continue being

so as long as the miraculous water still flows, as long as it still gives us

liveliness and good health.”

“Miraculous water”, Slivensko delo, 1989, #18, p. 9

Over the past 120 years the resort of Sliven Mineral Baths has been transforming following what appears to be a spiralling trajectory – having reached its outermost point of development a few decades ago it has since been gradually returning to nature, erasing any previous signs of land or water management efforts in the process. With the advancement of time its manmade structures are descending into (or ascending towards) a new form of existence, one of unresisting dissolution into a small island of cultured nature now gone feral.

Divine waters

At the end of the 19th century the thermal baths near the city of Sliven consisted of two Ottoman era masonry buildings believed to be resting upon the foundations of a Roman bath, similar to other thermal baths across the country. A limited number of amenities accommodated the needs of the visitors - a guest house, a pub, a café and a stable all linked into one continuous, narrow, nearly 150-meter long building, capped at both ends with the two public baths – male and female. The round pools of the baths, submerged below ground level, filled naturally with thermal water which appeared to spring through the gaps between the stone blocks on the pool floor. A nearby outdoor pool called “Bozha banya” (God’s bath) made for an additional informal bathing facility, while resting atop of the most abundant water source.

“The Roman Bath” – the only remaining building from the Ottoman period. May 2021

The mineral waters emerged in an open field forming a wetland area as they flowed out uncaptured. The waters of the different springs varied in their chemical composition and temperatures, and each was assigned a specific folk name – The Swamp, The Iron Well, The God’s Bath, The Rails, The Female Bath, The Male Bath and a few more which names were likely unrecorded.

In response to the 1891’s decree, declaring the exclusive state ownership of all mineral springs in the country and outlining the specific condition under which municipalities could request to utilize them, the municipality of the city of Sliven launched a procedure that would secure its rights to manage the springs for an indefinite period of time. Within the course of 5 years the waters of the various springs were captured and merged to form a single source, plans were drawn for the construction of a new thermal bath and a hotel, and the surrounding marshes were partially drained to make way for a public park. The new thermal bath was inaugurated in 1902, becoming the first modern facility of this kind in the country. With a single exception, all Ottoman era buildings were demolished and “Bozha Banya” was cleared to make way for the construction of the new spring catchment.

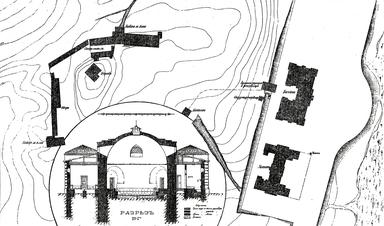

Site plan of the old and new thermal baths, and a section through the main pool

of the new building.

G. Kozarev, Magazine of the Bulgarian Architecture and

Engineering Association, Sofia 1902, appendix

Order and healing

“The road leading to the baths and their natural settings are extremely

beautiful, but their poor structure and the dirty pools are reducing

significantly their merits”

“Sliven’s thermal baths”, Medical review, 1888, #4

With similar accounts widespread across the country at the time, a number of articles soon appeared in specialized and popular editorials offering detailed recommendations for the improvement and management of thermal baths. Statistics were called for, alongside scientific surveys, to help quantify just about every aspect of the bathing experience. Beyond the usual hydrogeological analyses or visitor statistics, the spatial experience was also carefully measured and later contained within a set of rules applied from the public baths’ interior proportions to the landscaping of the private gardens of resort cottages. The last component to be encased in charts was the healing and recovery of the visitors, which could only be studied within a fully modernized bathing infrastructure. The set of treatment rules that ensued attempted to quantify the healing qualities of the thermal waters and was specific to each thermal bath where patients could be observed over extended periods time.

The recovery rates for a number of conditions treated in the thermal bath under

medical supervision.

Dr. Iv. S. Stanchev. Sliven Mineral baths, 1936

Shortly after the opening of the bathhouse in 1902, Sliven’s municipality proposed to develop several of the adjacent sites into a holiday village. As economic uncertainties coincided with the initiative and a renewed attempt to sell the land plots in 1930 did not attract a greater number of buyers, some of the plots were merged and sold to organizations that were willing to erect collective holiday and rehabilitation homes for their employees. By the mid 1930’s a new hotel and several holiday homes were already built, able to accommodate a few hundred visitors at a time.

In Sliven, clinical observations of around 2,000 patients were conducted over the course of 10 years, at the end of which the susceptibility of certain conditions to be treated successfully with the local thermal waters was to some extend determined. The research findings, alongside a set of bathing, water intake and dietary recommendations were published in 1936 and became the basis of the therapeutic procedures practiced in the balneological resort.

The collective holiday homes, literally called “rest-and-recovery homes”, operated under the supervision of medical staff that assigned treatment and assisted the recovery of the visitors, also referred to as “workers under treatment”. Despite the resort of Sliven Mineral Baths being a popular place for leisure and recreation, the workers staying at the holiday homes observed a strict daily routine of alternating portions of bathing, rest, meals and physical exercise. For a period of 20 days, a recovery plan assumed control of almost every aspect of the human body – from the mandatory intake of 3,500 calories per day to the bathing sessions measured by the minute, where no motion under water was allowed.

Ground level and section view of the thermal bath at Sliven Mineral Baths. The building designed by P. Momchilov and H. Meyer was completed in 1902 and extended in 1940. It consists of identical female and male sections, each with a large hot pool, a small cold pool (at the front corners), private baths, shower area and changing rooms. Additional treatment facilities were located on the upper level

Culture and pastries

“The only place is a cinema that screens old movies – nothing else.”

Slav Kolev, Sliven Mineral Baths could become a popular resort, Slivensko delo,

03.09.1970, #104, p. 4

“But the visitor pointed out that in the vicinity of the resort, even though the

number of guests continues to grow steadily, there isn’t a single pastry

shop.”

Mityo Mitev, A living connection, Slivensko delo, 09.06.1981, #54, p. 3

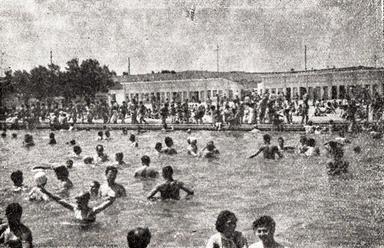

The years after the Second World War saw the collectivization of the properties at the Mineral Baths and the restructuring of their operations. Several new holiday homes were built to accommodate a growing number of workers eligible for treatment and recovery at the Baths, bringing the accommodation capacity to just above a thousand visitors at a time. Some of the former “rest-and-recovery” homes were transformed into fully functional balneosanatoria with thermal water procedures now available in-house. By the mid 1960’s the visits at the old thermal bath also increased, reaching 600,000 per year. A popular place for day trips from the city, the resort’s expanding infrastructure now included an outdoor mineral water pool, student camping grounds, an outdoor cinema with 400 seats, several restaurants and a number of pavilions selling all kinds of goods.

Outdoor thermal water pool

Д. Н. Кочанков, [D. N. Kochakov], Сливенски минерални бани [Sliven Mineral

Baths]. София: Медицина и физкултура, 1962

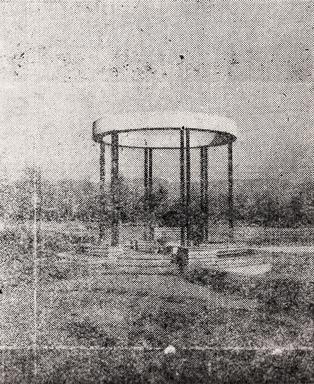

Garden pavilion on the “Island”

IV традиционен лекоатлетически крос на Сливенските минерални бани [4th annual

running race at the Sliven Mineral Baths], Sliven: ОС на БСФС, 1968

The grand ambitions for the future of the resort peaked at the end of the 1960’s when Glavproekt-Sofia cooperated with the Municipality of Sliven in drawing the plans for the resort’s expansion. The future development was divided into several zones, the central zone envisioning a community center (literally called “House of Culture”) with a cinema hall, linked to a new thermal bath via a thermal water drinking hall. The old thermal bath would retain its hygienic functions only.

North from the main road and at a sufficient distance from the new and existing balneosanatoria would be positioned the entertainment area, next to the existing outdoor pool. This zone included an outdoor theater, pastry shops and retail. The land plots west from the outdoor pool were to be designated for a holiday village consisting of 70 cottages.

The most ambitious part of the plan was the construction of new clusters of balneosanatoria and the extension of the existing ones increasing the capacity of the resort with additional 11,500 beds, or a 10-fold increase. The new balneosanatoria were to be housed in 3, 4 and 5-story blocks, connected via interlocking single story levels, creating a network of intimate courtyards.

None of the project components was ever realized. Ten years after the concept was developed, the visitors who stayed for treatment did not exceed 12,000 for the entire year. While certainly effort was made to make the resort a more desirable destination, those who spent there long periods of time for treatment found the amenities insufficient to make their stay comfortable. The possibilities to engage in anything other than walks in the park and an occasional meal in one of the three restaurants remained limited.

A Palace of Health

By the 1980’s the resort, expanded a few decades earlier to make accessible the curative qualities of the natural resource, started to transform into a burdensome infrastructure difficult to maintain by a state struggling with the ambitious projects of its own making. Visitors’ complaints and investigations into the mishandling of infrastructural projects at the Mineral Baths likely signalled more serious problems at a time when criticism of state and municipal institutions was rarely voiced.

Against a background of impending economic crisis and failing resort facilities nearby, a project for a large balneosanatorium was conceived, eventually breaking ground in 1985. Intended to be operated by the Council of the Bulgarian Professional Unions, the project was designed to accommodate 270 patients that would benefit from a state of the art treatment and rehabilitation wing, a 500 sq. m. indoor swimming pool, a 250-seat auditorium, a 300-seat restaurant, a library and a reading room, a bowling, a gym, a night club and a number of other communal areas.

“A Palace of Health”. The balneosanatorium of the Council of the Bulgarian Professional Unions after 10 years of construction was abandoned in the mid-90’s, nearly completed. May 2021

Despite shortages in the supply of building materials and unresolved infrastructural issues, the construction went ahead and continued for nearly 10 years only to stop short of completing the interiors. The undertaking, marked by a remarkable determination, continued to progress, while the remaining infrastructures of the resort were declining, seeing fewer visitors each year.

By the mid 1990’s the majority of the buildings needed a major upgrade and most of the facilities operated only during the summer months, if not already permanently closed. Changes in property ownership gradually started to fragment the resort, once managed by a single local entity under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health. The following 20 years were marked by sporadic efforts to maintain some of the buildings while their neighbors were left to be cared for by nature.

“Are you and investor?”

Upon setting up our photo and sound recording equipment a man approaches with an energetic pace and, without greeting, directly inquires if we are investors of some kind, here to rescue the thermal bath from its prolonged state of abandonment. As it became obvious that we are unlikely to be the old bath’s future saviors, our new companion descends into a monologue of general discontent, bringing up the economic and political grievances of the past few decades, with the occasional mention of the current ruling elites.

In their paper “Healing waters: infrastructure and capitalist fantasies in the socialist ruins of rural Bulgaria” Stefan Dorondel and Stelu Şerban (2019) describe what at first appears to be a curious episode, but in reality is an all too common response to the sight of foreign visitors in Bulgarian regions unable to recover after years of economic decline – the hope that prosperity will return, brought back by the benevolent will of a foreign investor, able to recognize the region’s potential.

“A Palace of Health”. The balneosanatorium of the Council of the Bulgarian Professional Unions after 10 years of construction was abandoned in the mid-90’s, nearly completed. May 2021

The former resort bus stop. In the 60’s 24-hour bus service operated between the resort and the city of Sliven. January 2021

In Sliven, an investor has probably already seized on the valuable resource, but not necessarily in exchange for investments in the public infrastructure. The only accessible mineral water fountain goes dry every morning up until lunchtime. No signage has been posted and unaware visitors leave with their bottles empty, not knowing that the water would come back in the afternoon in order to disappear again in the next morning. At 7:30 am, when we arrive at the Mineral Baths, the water fountain is already dry. Two patients sitting in front of the overgrown gardens of the nearby rehabilitation clinic inform us that the thermal water is redirected every morning to a private property across the road sporting an outdoor pool. The clinic itself has no access to the thermal water.

* * *

Barn swallow’s nest in the shower area of the thermal bath. January 2021

Against a backdrop of what ultimately is perceived as a negative process – the loss of order and completeness and the gradual disintegration of manmade infrastructures - a small ecosystem has been weaving its complex relationships and interdependencies, setting foot where humans no longer do. In a sea of arable land altered for millenia, a small island of feral plant life has been thriving, having conquered the former park grounds of the resort. The park, a prior piece of managed land itself, had claimed a century earlier an area covered by marshes formed by the spillover of the uncaptured thermal springs.

The thermal waters, despite being inaccessible but for a few, have been infiltrating their way back to their former territories of natural outflow. The water reservoirs and pumps left unattended for years have started giving in to the corrosive forces of the thermal waters, causing leakages and breakages along the nearly defunct supply network. The water, no longer used for the balneosanatoria, flows out undisturbed, springing from broken pipes and rusting pump rooms, flooding the grounds of the old thermal bath where a wetland once stretched.

Literature

IV Традиционен лекоатлетически крос на Сливенските минерални бани [4th annual running race at the Sliven Mineral Baths], Sliven: ОС на БСФС - Сливен

Азманов, Асен д-р [Azmanov, Asen Dr.]. Българските минерални извори [Bulgarian mineral springs], 1940, Sofia: Държавна печатница

Ангелов, Георги [Angelov, Georgi]. “Живата връзка“ [Living connection], Сливенско дело, 9 May 1981, #54

Ватев, Стефан [Vatev, Stefan]. Естествени лечебни богатства [Natural healing resources], 1904, Vidin: Печатница на Д. С. Балев

„Вълшебната вода“ [Magical water], Сливенско дело, 1989, #18

Гочев, Гочо [Gochev, Gocho]. История на Сливенските минерални бани [History of Sliven Mineral Baths], Sliven: Жажда, 2015

„Дворецът на минералните бани“ [The Palace at the Mineral Baths], Сливенско дело, 6 July 1990, #51

Джабаков, Ив. д-р [Djabakov, Iv. Dr.]. Курортът Сливенски минерални бани [Sliven mineral baths], (brochure, undated, after 1971.)

Димитров, В. [Dimitrov, V.]. „Чрез лечебността на водата – към здраве и сила!“ [ Health and strength from the healing waters!], Изток, 3 Sep 1939, #235

Закон за топлите и студените минерални води [Hot and cold mineral springs decree]. Държавен вестник, year XIII, 13 Dec. 1891, #273

Source: Sever +

Книга за диагнозите и лечението на болни с решение на медицинската комисия към Ямболската минерална баня 1936-1945 година [Diagnoses and treatment, Medical committee at the Yambol Mineral Bath 1936-1945]. Archives State Agency - Yambol, Ф. 47К, оп. 2, а.е. 7

Козарев, Георги [Kozarev, Georgi]. „Новозастроените Градски минерални бани (Лъджи) при град Сливен“ [The newly built thermal bath near Sliven], Magazine of the Bulgarian Architecture and Engineering Association, year 7, vol. 7-9, Sofia: 1902

Колев, Слав [Kolev, Slav]. „За да станат Сливенските минерални бани желан курорт...“ [Sliven Mineral Baths could become a popular resort], Сливенско дело, 3 Sep 1970, #104

Кочанков, Д. Н. [Kochankov, D. N.]. Сливенски минерални бани [Sliven Mineral Baths], 1962, Sofia: Медицина и физкултура

„Минералните ни бани“ [Our mineral baths]. Изток, 1940, #281

Найденович, Ал. [Naydenovich, Al.] „Сливенските лъджи“ [Sliven’s thermal baths], Медицински преглед [Medical review], 1888, #4

Николова, Ирина; Димитрина Тодорова [Nikolova, Irina; Dimitrina Todorova]. “Да подадем ръка на Сливенските минерални бани” [Let's stand by ...the Sliven Mineral Baths], 23 May 1987, #60

Николова, Мария [Nikolova , Maria], „Дворец на здравето“ [A Palace of Health], Сливенско дело, 24 Nov 1989, #47

Петленски, Димитър [Petlenski, Dimitar]. “Сливенските минерални бани - познати и непознати” [The known and lesser-known Sliven Mineral Baths], Сливенско дело, 9 Mar. 1982 #28

Протокол от заседание на Сливенско общинско управление №30 [Sliven Municipal Council meeting report #30], 14 July 1903, Archives State Agency – Sliven, Ф. 46К, оп. 1, а.е. 21, л. 190-201

Протокол от заседание на Сливенско общинско управление №26 [Sliven Municipal Council meeting report #26], 28 Oct 1905, Archives State Agency – Sliven, Ф. 46К, оп. 1, а.е. 24, л. 286-289

Протокол от заседание на Сливенско общинско управление №31 [Sliven Municipal Council meeting report #31], 28 Nov 1905, Archives State Agency – Sliven, Ф. 46К, оп. 1, а.е. 24, л. 318-320

Рандев, Евгений [Randev, Evgeny]. Състояние и перспективи за развитие на курортното лечение в Сливенските минерални бани [New resort treatment perspectives at Sliven Mineral Baths], Dissertation, 1994, University of Economics - Varna

Руснаков, Костадин [Rusnakov, Kostadin]. Сливенските минерални бани – съвременен курортен комплекс [Sliven Mineral Bath – a contemporary resort], Сливенско дело, 1 Jan 1969, #128

Станчев, Ив. С.[Stanchev, Iv. S.]. Сливенски минерални бани [Sliven Mineral baths], Sliven: Курортно бюро при Сливенската община, 1936

Stefan Dorondel & Stelu Şerban (2019): Healing waters: infrastructure and capitalist fantasies in the socialist ruins of rural Bulgaria, Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue canadienne d'études du développement

Source: doi.org

Табаков, Симеон [Tabakov, Simeon]. Опит за историята на град Сливен [On the history of the city of Sliven], Sofia: Отечествен фронт, 1986

Червенкова, Милка [Chervenkova, Milka]. Сливенски минерални бани (1878-1944) [Sliven Mineral Baths (1878-1944)], Архивен преглед, 1998, #3-4